Things were very different in July 2014 during the last Gaza war.

CNN's

Senior International Correspondent Nic Robertson first visited Gaza two

decades ago. Since then he has returned many times.

Israeli

jets were pounding the small strip of land, destroying buildings and

killing fighters and civilians in response to Hamas rocket attacks.

Let me take you back for a moment: The war had really started a few hundred miles away in the West Bank, when three Israeli teens were abducted and murdered. Israel blamed Hamas.

The retaliatory abduction and murder of a Palestinian teen wound tensions in the region to a fever pitch.

There

followed a dramatic escalation in the number of rockets Hamas was

firing into Israel and after a failed attempt by militants to storm into

its territory, Israel launched the so-called Operation Protective Edge.

The war lasted six or so weeks and by

the time a ceasefire was agreed, some 2,100 Palestinians, mostly

civilians, and 68 Israelis, mostly soldiers, had been killed.

Israeli official: Hamas a major obstacle in rebuilding Gaza 02:53

At its height, the crossing into Gaza was often closed, and slowed to a crawl at other times.

So,

the first surprise was a relatively pain-free crossing from Israel

through the Erez junction crossing, not a first but always nice.

To get in to Gaza, you need to be a credentialed aid worker or journalist -- some diplomats gain access too.

It's

like an airport but you carry your own bags all the way. After passport

control, there's no jet way to a waiting plane, instead long metal

corridors funnel you to the entry turnstiles.

The logistics of getting into Gaza 01:46

The surprise was small but very pleasant.

At

a turnstile, Israeli border guards remotely activated a door to the

side and, with our bags teetering dangerously on an overladen cart, we

wobbled through.

We'd been saved from humping and heaving them on and off the trolley through the turnstile.

Next came the kilometer-long cage that contains the concrete walkway to the Gazan gatekeepers.

Nice surprise two, a motorbike trailing a big baggage barrow was waiting.

Once

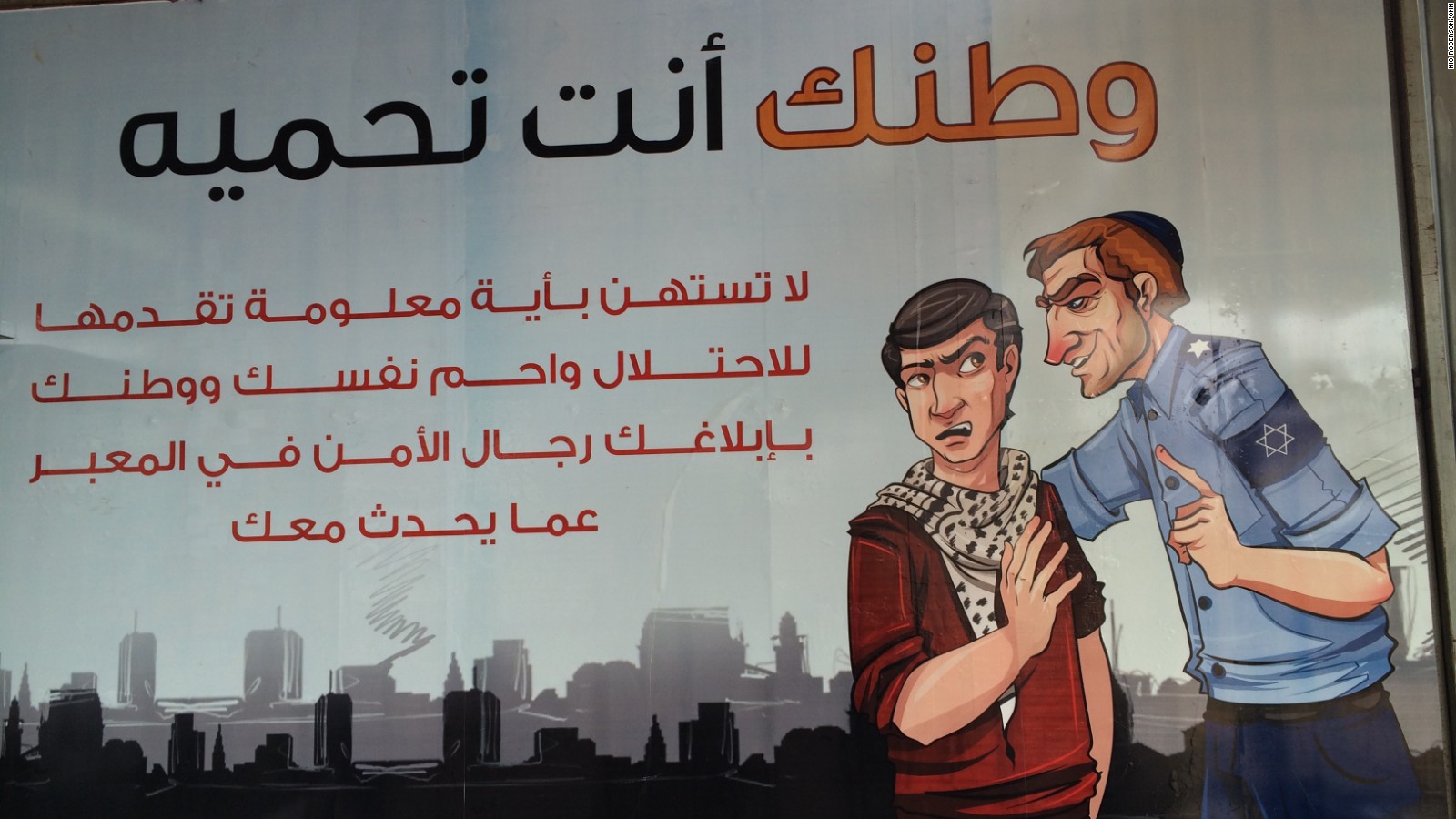

loaded, we sped towards the Palestinian passport checkers, past a

poster warning departing Palestinians not to be pressured by Israeli

police.

Poster at the border crossing between Israel and Gaza warning Palestinians not to be intimidated by Israeli police.

As

if a reminder were needed, trust between Palestinian and Israeli

officials is at a low ebb. The sprawling but secure crossing complex is a

sterile statement on how that gulf is bridged.

I won't count the surprises, but for the record the next is number three.

Banksy -- the elusive British graffiti artist -- had been to Gaza recently.

Before anyone noticed, he sneaked in, left his mark, and was gone.

There were four works, and by chance we drove past a couple. One has

already been impounded by the police.

Controversy

surrounds ownership: Banksy gifted them to Gaza, while in New York or

London they could have made him a tidy six or seven-figure sum.

I

saw his graffiti cat, sprayed on a house wall and freshly caged. His

lucky "owner" had just erected a chicken coop structure -- a

wood-and-wire mess -- around the artwork.

A Gazan man erects a chickenwire cage around a Banksy graffiti artwork.

It

looked to me like it would barely keep out a fox -- never mind a wily

cat burglar or committed thief. Anyway, it was a nice surprise and the

cute cat put a smile on my face.

I met Gaza's youthful and spring-legged Parkour team too. Not at all what you'd expect in a strip more famed for fighters than sportsmen.

But

there they were in their bright yellow T-shirts launching themselves in

great death-defying salvos atop the crumpled concrete and angry twisted

rebar wreckage of last summer's war.

'I want to be free': Escaping Gaza through parkour 02:25

All

12 of them were committed to nothing more than the feeling of freedom

in flight -- however brief -- and the hope that this sport could

catapult them beyond Gaza's borders to a better life.

This possibility came maybe a little closer recently.

The

team was spotted by the popular Middle East TV show "Arabs Got Talent,"

which might just have the pull to make their dreams come true and get

them out of Gaza -- if they can show they've got real talent.

In

a tiny strip just 41 kilometers (25 miles) long, by six to 12

kilometers across, crammed with 1.8 million people, most of them under

30, it's perhaps no surprise that conditions should throw up a Parkour

team.

Competitive soccer, which for so many aspiring youngsters worldwide offers a ticket to riches, always seemed a nonstarter here.

In

these youngsters, I found something else perhaps unsurprising: Unlike

their parents, they have little understanding of the Israelis beyond the

fence -- because they have no connection with them.

Gaza's Parkour team flip through the rubble.

Some

of the team were still children, not even in high school, when Israel

pulled out of Gaza in 2005. Their parents were once able to pass to

Israel for work with relative ease, but since withdrawal the wall has

become a barrier only their imagination can leap. Beyond it they fear

evils that ignorance amplifies.

Their parents had relationships with Israelis, understood them, knew them as people -- not as figures of fear and hate.

When

I first came to Gaza two decades ago, the Erez junction crossing of

today, with its steel corridors and caged walkways wasn't there. We

walked down the road past long lines of Palestinians on their way to

work in Israel. Today a tiny trickle passes through.

But

here's the next surprise. Well it was to me anyway. Abdu Salim, in his

sparkling, spanking new restaurant. There are pristine white

tablecloths, creases neatly rising from the wood beneath, and clean, oh

so clean.

That's of itself something a

little unexpected amid the dust and, sometimes, squalor that can be

Gaza. But the real surprise I had was when Abdu told me he bought this

place as the bombs were still falling last summer.

It was a hideously brave investment in a semi-derelict property in the middle of a war wrapped in an enduring conflict.

But

the gamble seems to be paying off, customers are coming not just

because it's clean and tidy but because the food, particularly his

shawarma, is so good. It has already achieved legendary status here. The

best in town we were told.

What I

wouldn't have guessed is where he earned his culinary chops. He told me

it was in Israel -- at restaurants in Tel Aviv and Jerusalem -- where he

used to work when the Erez crossing was more open.

Working

in kitchens there taught him not just how to make great food but helped

fuel and finance his ambition to open his own business. He employs 40

people now.

He remembers those days,

and understands Israelis well enough, he thinks, to get along with them.

He wants peace, not just because it's good for business but because he

can see the two sides moving further apart. But he's not sure his

leaders can deliver that peace.

Abdu

wasn't the only person of his generation I talked to whose fears

oscillate between anger at Israelis and frustration with their own

leaders. They fear what the future holds for their children, whose

estrangement from Israeli youth seems to be a one-way ticket to

continued conflict.

No comments:

Post a Comment